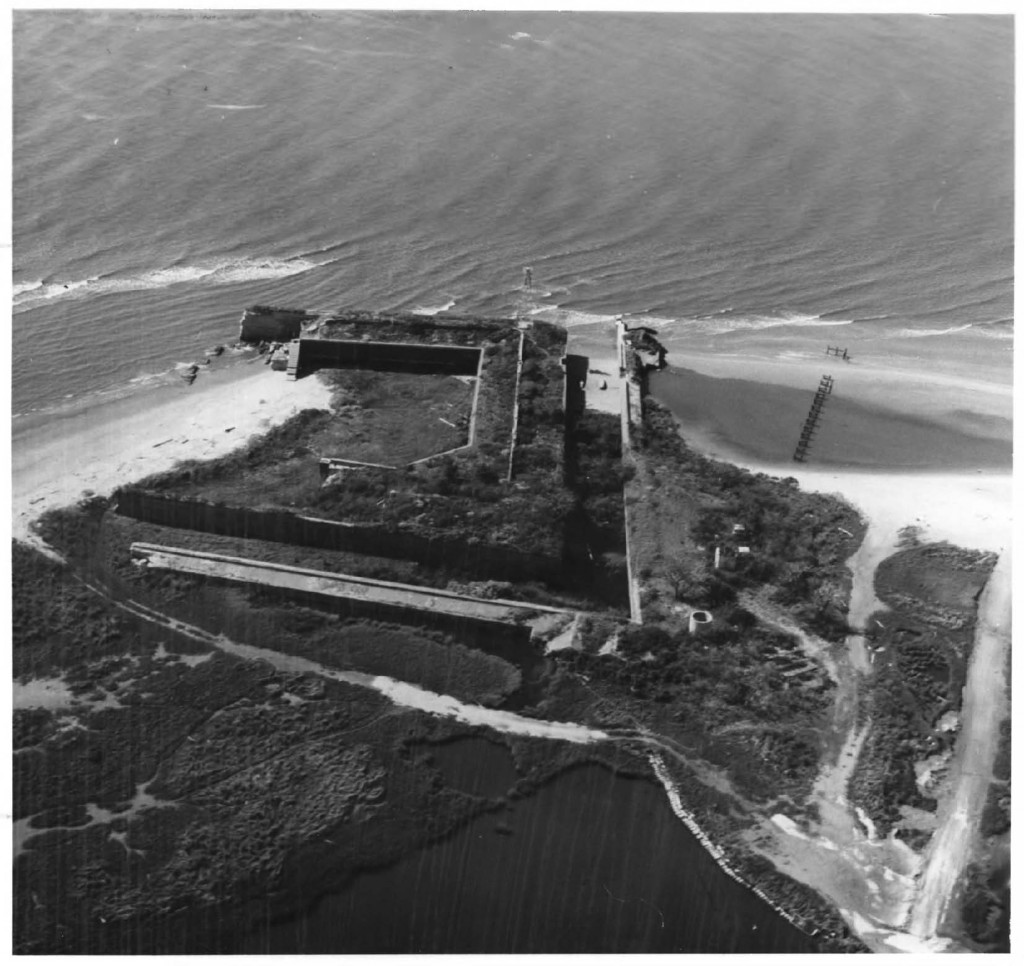

Fort Livingston is located on the western end of Grand Terre, facing Barataria Pass. At the outbreak of the Civil War, the fort had no weapons or troops. Confederate troops took it over in early 1861, possibly January or March. By July of that year, Confederate General David Twiggs indicated that the fort was manned by two companies of volunteers. In December of that year, 400 men manned one 32-pound rifled artillery piece, one 8-inch Columbiad, seven 24-pound howitzers, and four 12-pound howitzers.

Plans for Fort Livingston were prepared in Washington by Lieutenant H.G. Wright under the direction of Chief Engineer Colonel Joseph Gilbert Totten in 1841-42. The original design of the fort was a trapezium-shaped stronghold, surrounded by a wet ditch, and outworks on the land side. The walls were constructed of cemented shell faced with brick and granite trim. On top of the ramparts is the terreplain were cannons were mounted. The terreplain was fronted by a parapet, only a portion of which remains. Inside the ramparts, barrel vaulted chambers, or casemates, surround the court with viewholes for guns facing outward and doors with granite lintels opening to the courtyard. The original plans indicate that inside the casement were to be the soldiers’ quarters, officers’ guard room, guard room, prison, sutler’s room, artillery store room, magazine, carpenter shop, blacksmith’s shop with a forge, and a bakery with an oven. Exterior granite stairs were indicated to be on two sides of the court. What was probably a long ramp, which would have ascended the south wall, is also show on the original plans. In 1849 Captain J.G. Barnard, superintending engineer, prepared a sketch of a “piazza” to line the walls of the fort facing the courtyard. It consisted of slender iron columns with foliated capitals supporting an arched arcade with a tiled shed roof. If this “piazza” was ever constructed, there are no remnants of it today.

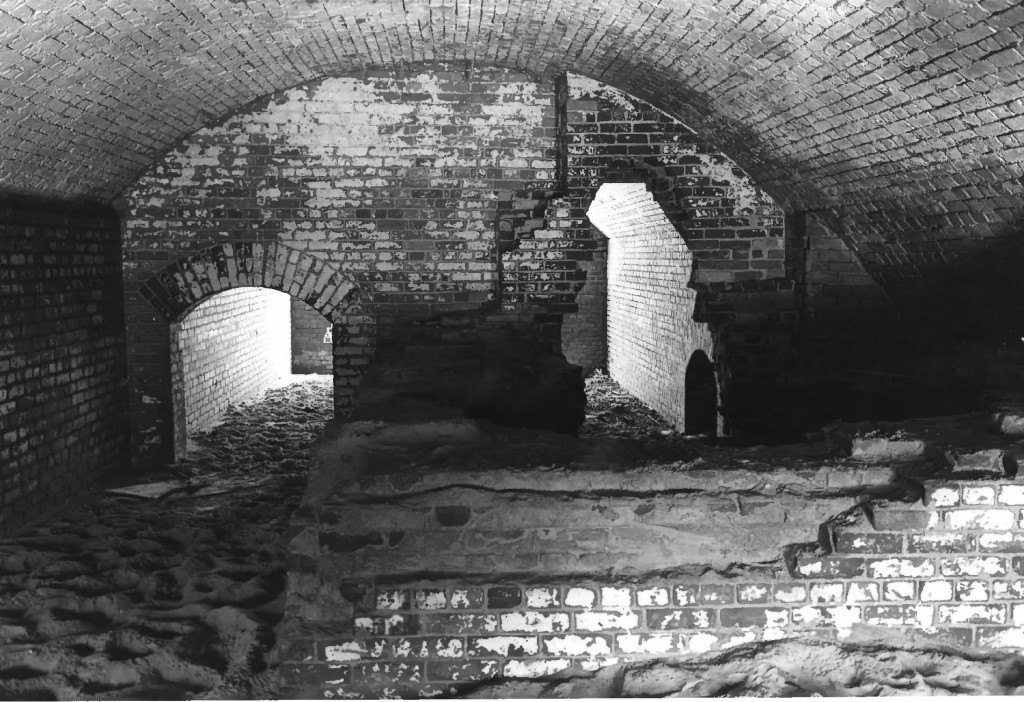

The fort was protected on the land side by a moat or wet ditch and a counterscarp, or outer wall, which was supported by arched and counter-arched revetments to strengthen the wall against bombardment. For additional protection, the outer wall was faced with a sloping earth glacis. Within the outerwork wall is a long tunnel-like covered way, or patrol path, called the counterscarp gallery, that provided protected exterior access along the complete distance of the land faces of the fort. Embrasures for small arms fire open form the interior passage way to the wet ditch. Powder magazines were also located in the counterscarp gallery. A drawbridge was designed to cross the moat from the top of the outer wall to the entrance on the north side of the fort. Having been constructed of wood, there are no remains of this bridge today.

The south face of the fort, fronting the gulf was completely demolished by the hurricane of 1915 and sand dunes now fill the court and casemates.

Fort Livingston is one of the largest coastal forts in Louisiana and is Louisiana’s only fort on the Gulf of Mexico. Excepting Fort Point in San Francisco, Fort Livingston is the western-most of the system of coastal defenses that line the east and Gulf coasts of the United States.

Ruin of the counterscarp gallery. A counterscarp gallery are tunnels that are built behind the counterscarp, or the outer wall of the fortification (National Park Service).

Fort Livingston was abandoned after the Civil War and although the War Department had interest in the fort and the Board of Engineers in Washington proposed modifications for the structure in 1870, it was returned the State of Louisiana in 1923.

Facing south towards the Gulf of Mexico, showing court facade of ramparts and doors with granite lintels. The doorways lead to casements (National Park Service).

Detail of the construction of Fort Livingston showing clam shells faced with brick (National Park Service).

More information: